A posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is a natural event, yet is a common cause of retinal tears. A PVD will happen to everyone as we age and onset is usually sudden.

Vitreous and Retina

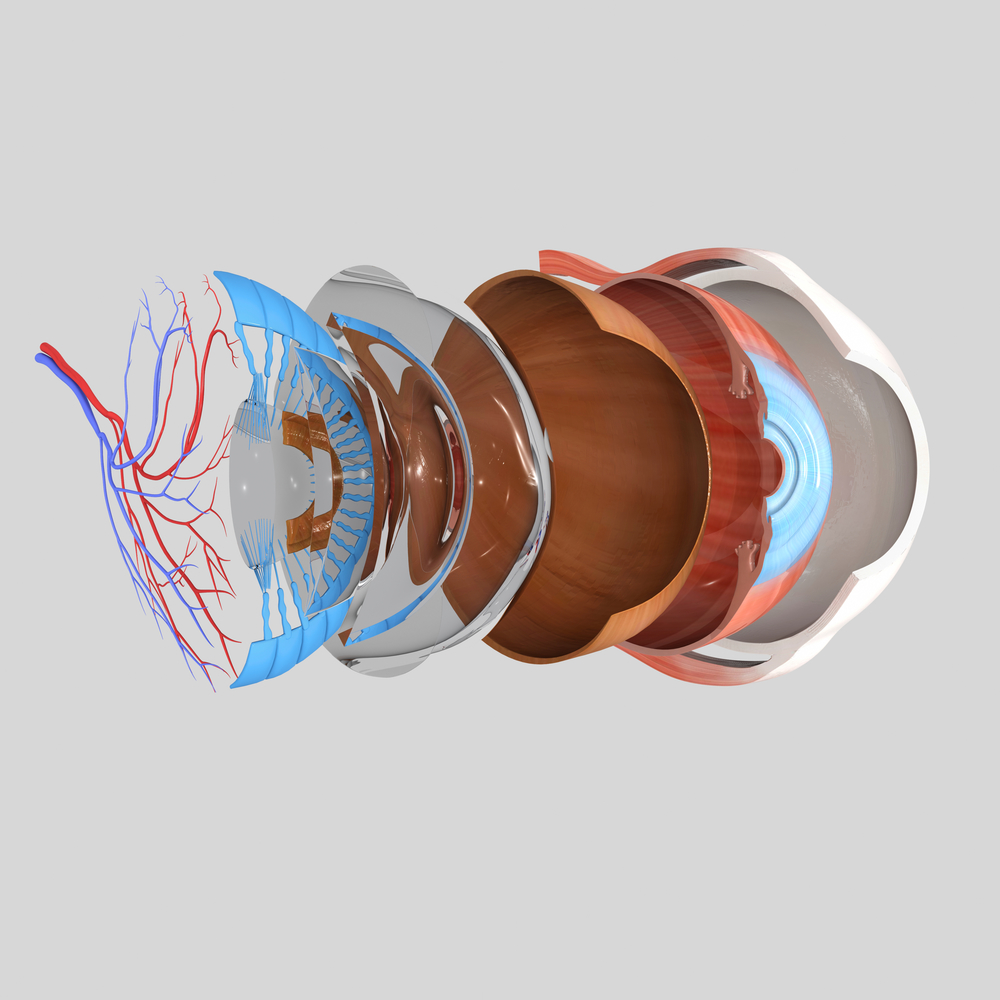

The vitreous, the watery gel that fills the eye, is naturally adherent to the retina. The retina being the light sensitive tissue which lines the inside of the eye.

Light enters the eye and gets focused on the retina. The retina captures the light and sends signals to our brain via the optic nerve to produce “vision.”

The vitreous is not renewed or replenished.

As we age, the proteins which make up the gel of the vitreous tend to break down. As a result, the vitreous becomes more fluid or watery. Cavities of water (think of pockets of air within Swiss cheese) form within the gel. Eventually the gel collapses on itself causing the posterior vitreous (the vitreous toward the back half of the eye) to pull away, or detach, from the retina.

The vitreous usually remains adherent to the retina in the front half of the eye.

Symptoms of PVD

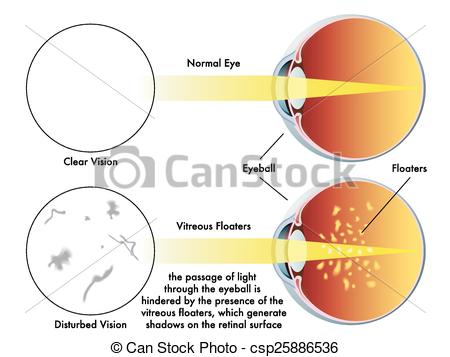

A posterior vitreous detachment usually causes flashes and floaters. Not everyone has symptoms.

Flashes are a result of the vitreous gently tugging on the retina as the vitreous moves with eye movement. This tugging can cause a tear.

Floaters develop either from a change in the optical qualities of the vitreous (shadows/spots can form due to protein breakdown), bleeding from a retinal tear or migration of cells from under the retina to the vitreous via a retinal tear.

There is no way to distinguish the cause of floaters without examination. The most benign scenario is PVD without a retinal tear.